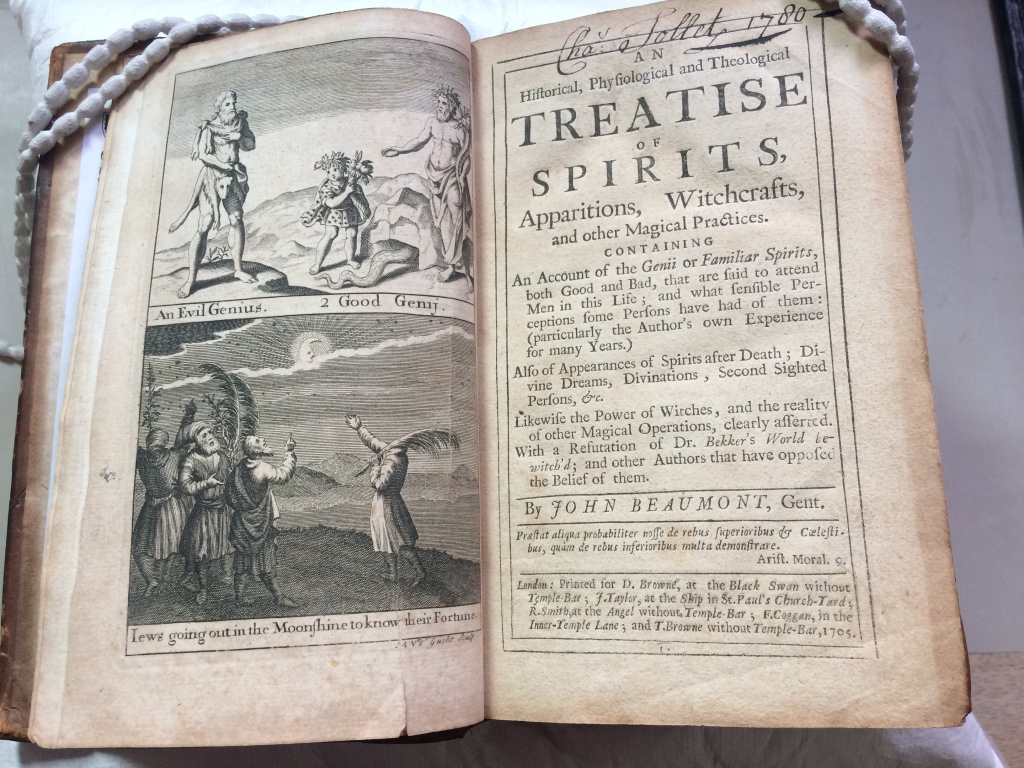

Earlier this year, the College received an intriguing little book in the post. An accompanying letter explained that it had been found among the possessions of the sender’s relative after their death. They believed it may have been acquired by accident or misadventure during an ancestor’s time at Cambridge, and so they were returning it to Trinity Hall. There is, sure enough, an ownership inscription on the title page which says ‘W. Territt Trinity Hall’, however it was never part of the College library collection!

The book belonged to William Territt (c1768-1836) who matriculated at Trinity Hall in 1786, obtaining a Bachelor in Law in 1792, followed by LLD in 1797. He embarked on a legal career and was to become Judge of the Court of Vice Admiralty in Bermuda between 1802 and 1815. He later returned to England to his family seat at Chilton Hall, Suffolk , and died aged 67 in 1836 [1].

Besides Territt, there are traces of one other former owner, Richard Belward(?) who has written his name (none too legibly) on the sides of the frontispiece. His initials ‘R.B’ are also stamped on the cover.

The book is the Chronological Tables of Europe. From the Nativity of our Saviour to the year 1703. [2] The engraved title page identifies ‘Colonel Parsons’ as the author, although, in fact, it is a translation and slight modification of Guillaume Marcel’s Tablettes Chronologiques, first printed in Paris in 1682.

Spotting a money-making opportunity, William Parsons (1658–c1725) a former English army officer, simplified Marcel’s complex layout and symbolic scheme, and reduced its size so that it was easily portable. His new format was a commercial success, and many editions followed, selling 4,000 copies in about a decade.

Each page of this remarkable pocket-sized book represents a century (1st to 17th), meticulously detailing the names and dates of monarchs and rulers. But what sets Parsons’ work apart are the mysterious symbols adorning its pages, offering insights into the character and fate of these historical figures. A fold-out chart provides the key so the reader can understand the symbols given in the tables.

Among the symbols, the sun, or sol, reigns supreme. Representing the most glorious of all characters, it signifies a ruler endowed with the greatest perfections—a monarch esteemed as a most accomplished ruler by historians; one example is Elizabeth I.

In contrast, the symbol for Saturn, resembling an ‘h’ shape, paints a grim picture. It denotes a cruel and bloody monarch. This has been applied to Elizabeth’s sister Mary I. Mary’s entry also has the dart and luna symbols (crescent moon) which signify misfortune, marked by adversity and hardship.

The symbol for Mars—a circle with an arrow—signifies a prince of good courage and a warrior who leaves a mark on the annals of history with their bravery. Suleiman the Magnificent is in this category.

The symbols provide an ingenious means to save space. Compact and lightweight, the book was designed for portability—a ready companion for the avid scholar or curious student. Its ingenious layout, paired with symbols for quick reference, made it a practical tool for navigating the complexities of European history. As it says on the title page:

“…digested into so very easie and exact a method, that any one may immediately find out either pope, emperour, or king, and thereby know in what time & kingdom he reign’d, who were his predecessours, contemp[ou]rs, & success[ou]rs, to what virtues or vices he was most inclinable, the good or ill success of his fortune, the manner & time of his death.”

This humble chronology serves as a reminder of our connection to the past. Through its pages, we not only uncover the stories of long-forgotten rulers, but can also trace the previous owners, bound together by a shared quest for knowledge. More than two hundred years after the book was purchased in Cambridge by a student at Trinity Hall, it has once again ‘returned’ to the College.

Jenni Lecky-Thompson

References

[1] Venn, J., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge, 1922.

[2] Marcel, Guillaume. Chronological Tables of Europe…. The VIth. Impression. London: printed for B. Barker at the White-Hart and C. King at the Judges Head in Westminster Hall, 1707.

![PERSEVE'RANCE.

n.s. [perseverance, Fr. perseverantia, Lat. This word was once improperly accented on the second syllable.]

Persistence in any design or attempt; steadiness in pursuits; constancy in progress. It is applied alike to good and ill. The king becoming graces,

Bounty, persev’rance, mercy, lowliness;

I have no relish of them.

Shakesp. Macbeth. Perseverance keeps honour bright:

To have done, is to hang quite out of fashion,

Like rusty mail in monumental mockery.

Shakespeare. They hate repentance more than perseverance in a fault.

King Charles. Wait the seasons of providence with patience and perseverance in the duties of our calling, what difficulties soever we may encounter.

L’Estrange. Patience and perseverance overcome the greatest difficulties.

Clarissa. And perseverance with his batter’d shield.

Brooke.](https://oldlibrarytrinityhall.files.wordpress.com/2021/11/img_2942.jpg?w=1024)