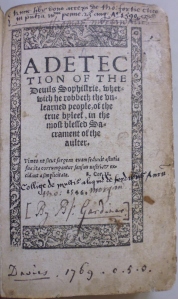

Title page of The Interpreter

The Old Library at Trinity Hall is home to many law texts including an unprepossessing book written by John Cowell. It is known as The Interpreter (1607); or to give it its pithy title, The interpreter: Or Booke containing the signification of words : Wherein is set foorth the true meaning of all, or the most part of such words and termes, as are mentioned in the lawe vvriters, or statutes of this victorious and renowned kingdome, requiring any exposition or interpretation. A worke not onely profitable, but necessary for such as desire throughly to be instructed in the knowledge of our lawes, statutes, or other antiquities (Yes I’ll stick to The Interpreter). It was one of the first English law dictionaries, so while you may think this would be an safely dull publication, it was to cause a scandal which would lead to the book’s suppression and public burning, and almost earnt the author the death penalty.

John Cowell was born in Landkey, Devon in 1552. He was educated at Eton on a scholarship, before going up to King’s College, Cambridge in 1570, aged 18. He was a Fellow of King’s from 1573 until 1595, and was appointed to the Regius Professorship of Civil Law in 1594. Two years later he became Master of Trinity Hall – a post he was to hold until his death in 1611. He was also vice-chancellor of Cambridge University between 1603 and 1604. The pinnacle of his career came in 1608 when the Archbishop of Canterbury Richard Bancroft, who was his friend and mentor, made him his vicar-general. This important position meant that he was judge of the ecclesiastic court.

Cowell’s dedication to Bancroft

Now on to the main story. The Interpreter was published in 1607 by university printer, John Legate (he rented a shop at the west end of Great St Mary’s Church), and it was dedicated to Bancroft.

As it says in Cowell’s preface, the book was intended as an academic work for the ‘advancement of knowledge’, and was unlikely to have been written with any political motivation. In fact, any controversy appeared to go unnoticed for more than two years.

Cowell’s definition of ‘prerogative’

The thing that landed Cowell in hot water was a handful of definitions contained in his dictionary, in particular ‘King’, ‘Parliament,’ ‘Prerogative’, ‘Recoveries’, and ‘Subsidies’.

So why were these so controversial? Cowell’s definitions appeared to support the idea of an absolute monarchy, which was above the law. This was controversial in a difficult political climate where the Crown and Parliament were vying for power. When the parliament met on 24 February 1609 James I’s attention was drawn towards The Interpreter. Sir Edwin Sandys described the book as “very ill-advised and indiscreet, tending to the disreputaton of the House, and the power of the common laws”. A committee was then formed later that month to consider the book and report to the House of Lords.

The Chief Justice Sir Edward Coke was one of a group of lawyers on this committee who attacked Cowell’s book. Coke perhaps felt some hostility or jealousy towards Cowell and disparagingly referred to him in letters as ‘Cow-heel’. The background to his antagonism was complex, but was rooted in Cowell’s criticism of Thomas Littleton’s scholarship, whom Coke greatly admired and had based his own work. It was also a battle between the common law courts and civil law courts, with Coke and Cowell on opposing sides.

The Interpreter was investigated and it looked for a time that Cowell would be executed. The indictment read:

Dr. Cowell, Professor of the Civil Law at Cambridge, writ a book called The Interpreter, rashly, dangerously and perniciously asserting certain heads to the overthrow and destruction of Parliaments, and the fundamental laws and government of the Kingdom.

There was much discussion of the book and of Cowell’s punishment in the Commons and Lords. While they debated the matter, James I asked Cowell to explain himself. The King then stepped in to denounce the book with a Royal proclamation. This in effect, took the matter out of the hands of parliament.

The proclamation order read:

When Men goe out of their Element, and meddle with Things above their Capacitie, themselves shall not onely goe astray and stumble in Darknesse, but will mislead also divers others with themselves into many Mistakings and Errours.. the Proofe whereof wee have lately had by a Booke written by Docteur Cowell.. by medling in Matters above his reach, he hath fallen in many Things to mistake and deceive himselfe.. in some Poynts very derogatory to the supreme Power of this Crowne; In other Cases mistaking the true State of the Parliament of this Kingdome.

People were prohibited from buying or reading The Interpreter and Cowell’s book is said to have been publicly burnt by the hangman on 26 March 1610. It was one of only around fifteen books that were consigned to the flames during the whole of the 59 year reign of James I.

Cowell was imprisoned for a while, but the case against him was soon dropped. James I apparently let it be known that Cowell was not to be prosecuted or harmed. He resigned his professorship on 25 May 1610 and died on 11 October 1611. He was buried in Trinity Hall Chapel and left bequests in his Will to Trinity Hall, King’s College, and to Cambridge University. These included his books and manuscripts which are held in the Old Library (possibly even his own copy of The Interpreter!).

Plaque commemorating Cowell in Trinity Hall Chapel

This was not the end of the story for Cowell’s dictionary. Many copies have survived and it was reissued in unexpurgated form 27 years later, in 1658. Fresh editions were also published in the 17th century.

Further reading

Boucher, Harold, King James’s suppression of The Interpreter and denouncement of Dr. Cowell (Harold I. Boucher, 1998).

Chrimes, S. B., ‘The Constitutional Ideas of Dr. John Cowell.’ The English Historical Review, vol. 64, no. 253, (1949): 461–487. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/556038

Hessayon, A., ‘Incendiary texts: book burning in England, c.1640 – c.1660′, Cromohs, 12 (2007): 1-25.

http://www.cromohs.unifi.it/12_2007/hessayon_incendtexts.html

Levack, Brian P., ‘Cowell, John (1554–1611), civil lawyer.’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (2004). Oxford University Press. Accessed 16 May 2018 at: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-6490

Simon, J., ‘Dr. Cowell’. The Cambridge Law Journal, vol. 26, no. 2 (1968): 260-272. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008197300088528

Wright, Nancy E., ‘John Cowell and the Interpreter: Law, Authority, and Attribution in Seventeenth-Century England,’ Australian Journal of Legal History vol. 1, no. 1 (1995): 11-36. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/ausleghis1&div=7&id=&page=