We are VERY grateful to our guest blogger, Dunstan Roberts, who has written this post for the Old Library blog. Dunstan is a graduate student at Trinity Hall. He has recently submitted a doctoral thesis on readers’ annotations in sixteenth-century religious books.

“A Detection of the Deuils Sophistrie”, a little-known work of sixteenth-century religious controversy, was published in 1546. The colourfully-named polemic was written by the then Master of Trinity Hall and Bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner (c.1495-1555), whose scholarly prowess and political nous placed him at the forefront of the conservative faction during much of the English Reformation.

What makes the College’s copy interesting is that one of its early readers has filled its margins with annotations—about three-thousand words of them, to be precise. Early modern readers often annotated books in order to improve comprehension and recollection, sometimes adding concise paraphrases and non-verbal notes.

But the annotations in the college’s copy of A Detection are not like this. They are far more pugnacious: a full-blown assault on Stephen Gardiner’s text, denouncing its theology, challenging its arguments, and refuting its patristic sources with rival interpretations and occasionally with rival sources.

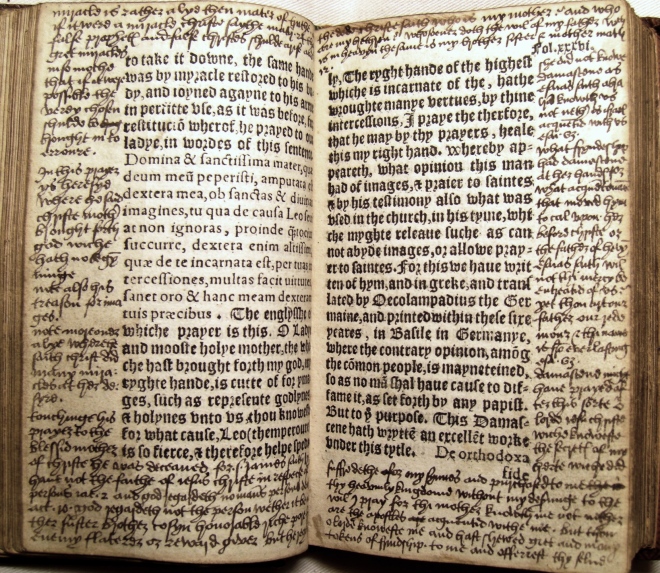

Stephen Gardiner, A Detection of the Deuils Sophistrie (1546). Trinity Hall, TH.G.I.1, sigs E3V-E4R.

Stephen Gardiner, A Detection of the Deuils Sophistrie (1546). Trinity Hall, TH.G.I.1, sigs E3V-E4R.

In more detail:

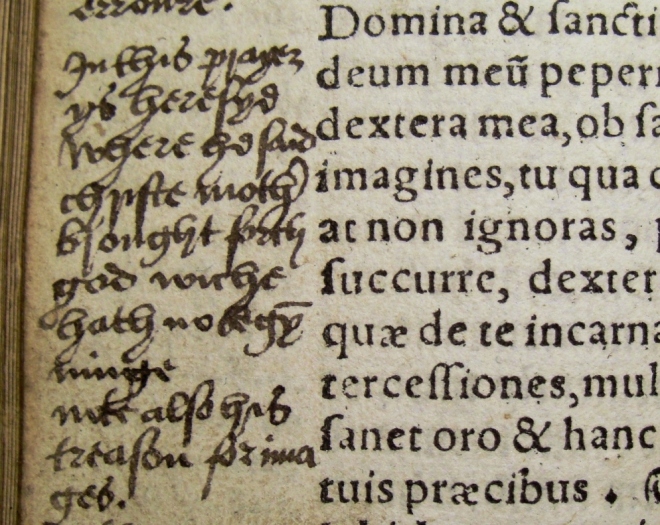

Sigs E3V-E4R: “In this prayer ys heresye where he said christe moth[er] brought forth god wiche hath no begy[n]ninge note also his treason for images”.

Sigs E3V-E4R: “In this prayer ys heresye where he said christe moth[er] brought forth god wiche hath no begy[n]ninge note also his treason for images”.

An analysis of the theological viewpoint of the annotations reveals a reader opposed to Gardiner’s Catholicism, but without any suggestion of religious radicalism: in short, a moderate Protestant.

So who was responsible for these unusual annotations? We are fortunate in this instance that the annotator has made his identity explicit through an ownership inscription at the rear of the book: ‘Tho[mas] morgan[us] Ap[u]d Myntie Diocaes[is]. Sa[rum]’. This gives us both a person and a location. The village of Minety (to give it its modern spelling) lies on the border between Wiltshire and Gloucestershire, about 7 miles north-west of Swindon, and falls within the diocese of Salisbury (known in Latin as Sarum). As for Thomas Morgan, he was vicar of Minety from 1582 to 1627, an impressive innings, especially by early-modern standards. We can find two students of his name at Oxford (none at Cambridge) during the decade prior to his installation at Minety: one at Jesus College and one at New Inn Hall (a medieval institution later subsumed into Balliol College). One of these men is very likely our man.

Sig. T4R (detail): “Tho[mas] morgan[us] Ap[u]d Myntie Diocaes[is] Sa[rum]” (Thomas Morgan of Minety, Salisbury Diocese).

Sig. T4R (detail): “Tho[mas] morgan[us] Ap[u]d Myntie Diocaes[is] Sa[rum]” (Thomas Morgan of Minety, Salisbury Diocese).

Thomas Morgan received his intellectual training at a time when university-educated clergy were seen as critical to the consolidation of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement and were highly sought after. Several colleges in Oxford and Cambridge (including Jesus College, Oxford, Morgan’s possible alma mater) were founded specifically to satisfy this demand. The theological education which the universities provided was conducted along explicitly disputatious lines; prospective clergy were taught how to debate and persuade, which sources to cite and what arguments to employ. Morgan’s patristic sources continued to be taught, even once their purely theological significance to Protestants had started to wane because they were useful for debating with Catholics. The members of this ‘new model clergy’ were not retained within centres of scholarship, but were dispatched into the provinces, where they could have a real impact.

It is within these historical circumstances which we should view this volume and its unusual contents. Whilst it is difficult to fathom the exact purpose of the annotations, there are several likely explanations. Combative annotations like this were sometimes used in the preparation of published rejoinders to controversial texts, although there is no specific evidence to suggest that Morgan was planning anything along these lines. He might, however, have been planning something slightly lower key, such as a sermon in which the former Bishop of Winchester was to be attacked. Or his motives might have been more private, attacking the text as an intellectual exercise, training himself for the larger fight against Catholicism.

There are many questions which remain unanswered and which will merit investigation in the future. We do not know what happened to the book during the centuries before the college acquired it in the latter half of the twentieth century. Nor, significantly, do we know how and why this volume survived when so many other sixteenth-century books perished. These details would be valuable in drawing together the complicated events to which this volume suggestively alludes. But we are, in the meantime, blessed with a remarkably vivid picture of the disputatious religious reading practices which came to the fore during the protracted years of religious turmoil in sixteenth century England.

Images by Dunstan Roberts.