Be careful what you promise! Way back in June I signed off my post about Hudibras promising one on the illustrations by Hogarth. Now, after a busy summer and a hectic Michaelmas term, here it finally is. However, I don’t expect you to have been waiting with bated breath (or I certainly hope you haven’t because… well, you wouldn’t be alive to read this now).

So what of William Hogarth, the illustrator of Hudibras? He was a Londoner of humble origins. Born in 1697 in Bartholomew Close, near Smithfield, he had the bustling city of London in his blood. His father made a meagre living by writing (an introduction to Latin and English “Thesaurarium trilingue publicum”, 1689) and taking in pupils. Life was very hard. From birth William was exposed to the harsh realities of a hand-to-mouth existence in the capital and to the multifarious characters who struggled to survive there (and who would later populate his satirical prints) and as a young man he was determined to better himself.

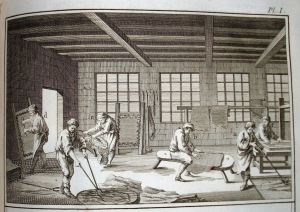

By 1714 he was apprenticed to a silver engraver, engraving shields and ciphers on forks, spoons, goblets and plates. However, he was bored and dreamed of better things. “Engraving on copper” was Hogarth said “at twenty years of age my utmost ambition” – and by 1720 he was on his way! He set up on his own as an engraver and paid the subscription to become a member of the new arts academy in St Martin’s Lane (which he attended in the evenings). There he honed his skills as a draughtsman and made valuable contacts. By 1722 he was employed on the team of book illustrators for La Motraye’s Travels. He also began producing topical prints and then started working on a group of small etchings illustrating Butler’s popular satirical poem Hudibras.

Hudibras was first published in 1663-78 and Hogarth may have known this poem from his childhood, It was still tremendously popular in the 1720s: it was a great favourite with the Tories and was constantly quoted in the Spectator. Seeing a money-making opportunity, in 1725 Hogarth worked on a series of twelve individual prints on Hudibras which were published by Philip Overton in February 1726. These prints were such a success that Hogarth used his earlier small engravings as illustrations for a new edition of the poem in May 1726. Our edition of Hudibras, which also contains Hogarth’s illustrations, was published in 1744 at the height of the artist’s fame when he was working on his series of paintings “Marriage a-la-mode”.

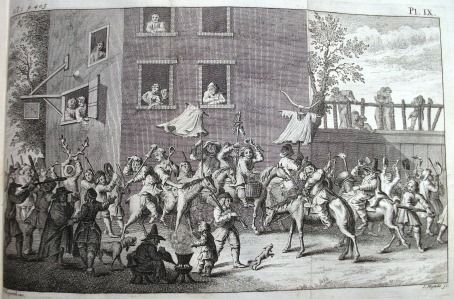

Samuel Butler and William Hogarth were a perfect fit. Hogarth’s illustrations are the visual embodiment of the author’s biting language, which satirised man’s hypocrisy and self-delusion. Hogarth’s scenes for Hudibras are lively, full of detail and merciless in their exposure of people’s failings. As Jenny Uglow points out in her biography, “the most vivid of all are the crowd scenes: the encounter with the bear-baiters, the skimmington…”

This was an art that showed the ordinary English men and women of the time without idealization or sentimentality. The artist’s democratic eye lampooned the great and the good or the man in the street with equal vigour. His work is skilful, full of detail and never boring and its popular appeal propelled Hogarth up the social scale to great success.

Hogarth’s work and quirky imagery has echoed down the centuries and in the 1960’s it resurfaced in the work of one of Britain’s foremost contemporary artists, David Hockney. Hogarth was an early inspiration for Hockney who produced a series of contemporary etchings on the theme of the Rake’s progress (1960-61). His commission to do the designs for the Glyndebourne production of the opera of Rake’s Progress in 1974 reinvigorated his art and Hogarth’s direct inspiration can be seen in the painting “Kerby” (1975) now in the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Like Hogarth, Hockney rose from relatively humble origins to become a leading figure in the art establishment. His own very English eye has resulted in work which has met with great popularity. Perhaps his most famous work is Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1970-71) which is a contemporary take on the work of another great English artist, Thomas Gainsborough. And, like Hogarth, it is Hockney’s skill as a draughtsman that has underpinned his work in the fields of painting, portraiture and printmaking. Hockney has also explored the use of technological innovations such as Polaroid photography, fax machines and the drawing application called Brushes for iPhones and iPads. I wonder if Hogarth would have done the same had he been alive today?

If you would like to see Hockney’s latest work then you may do so at the Royal Academy in the New Year: “David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture” is on from 21 January to 9 April 2012.

References:

William Hogarth article on Wikipedia

“Hogarth: a life and world” by Jenny Uglow. London: Faber & Faber, 1997

David Hockney article on Wikipedia

David Hockney’s official website

“David Hockney” by Marco Livingstone. London, Thames & Hudson, 1996